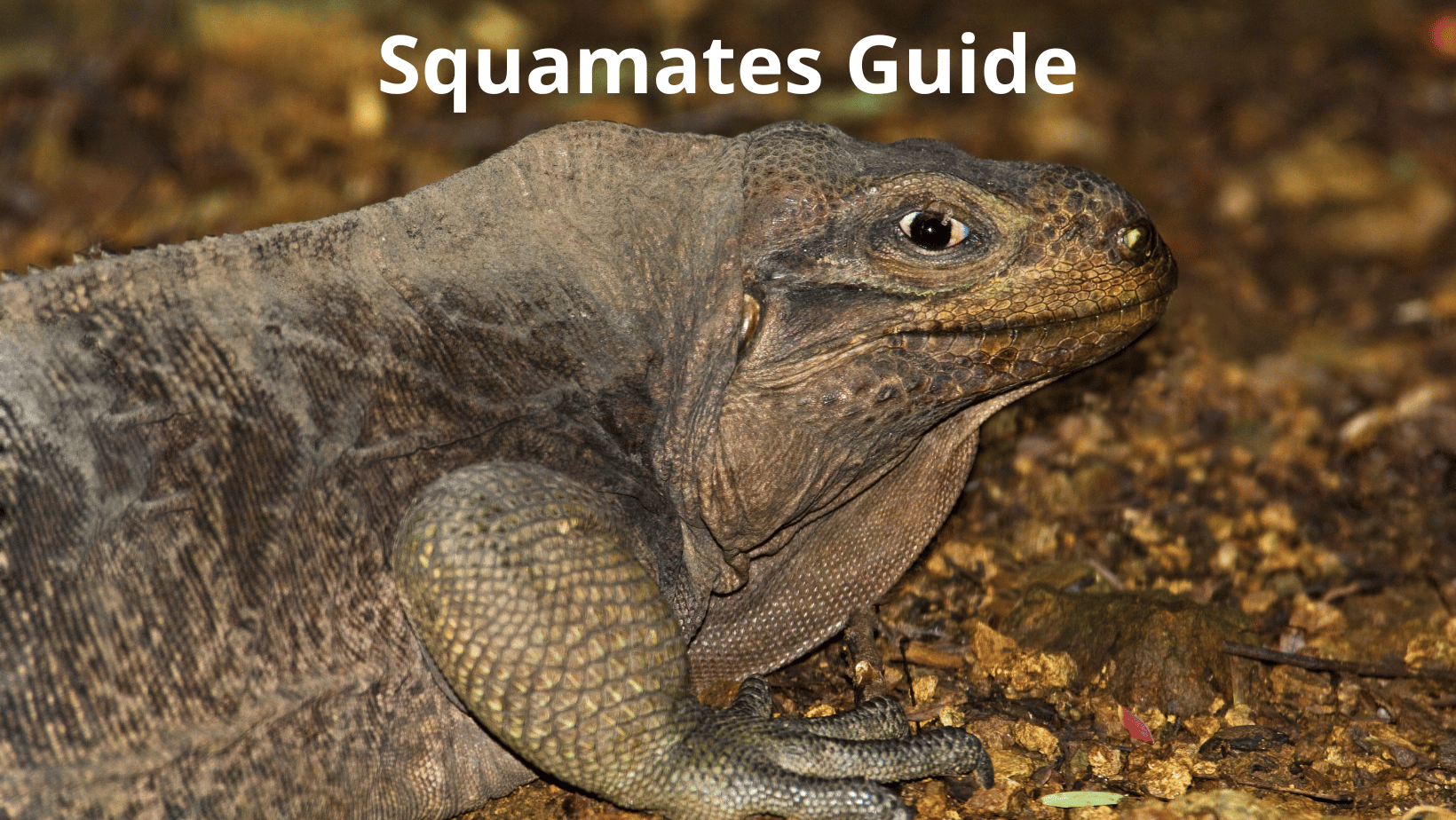

Squamates represent a vast and fascinating segment of the reptilian world. With a lineage that spans millions of years, these reptiles have evolved into a plethora of forms and occupy a myriad of habitats.

This introductory section sets the stage for a deeper dive into the incredible world of squamates, exploring their overall significance and the breathtaking diversity they present.

A Glimpse into the World of Squamates

Squamates, commonly recognized as lizards and snakes, are an intriguing group of reptiles that have fascinated biologists and enthusiasts alike for centuries.

Their adaptability and diverse range of ecological roles allow them to thrive in nearly every terrestrial habitat on Earth, from scorching deserts to dense tropical rainforests.

Their evolutionary history and unique biological characteristics not only make them subjects of academic interest but also underline their importance in maintaining ecological balances.

They act as predators, controlling populations of insects and small mammals, and also serve as prey for many larger animals, underlining their crucial role in food chains.

Diversity Beyond Imagination: Species and Families Galore

When it comes to sheer numbers, squamates are truly astounding. Boasting around 10,900 extant species, they form one of the most diverse groups within the vertebrate lineage.

This vast number is distributed across a staggering 60 families, each showcasing a unique blend of characteristics, behaviors, and adaptations.

This diversity not only highlights the evolutionary success of squamates but also hints at the myriad ecological roles they play across ecosystems.

From the nimble geckos that scurry on our walls to the majestic pythons that dominate their habitats, the range and breadth of species within this group are a testament to nature’s ingenuity.

As we delve deeper into this guide, readers will journey across the different families and groups of squamates, gaining insights into their unique attributes, evolutionary tales, and significance in the broader spectrum of biodiversity.

Amphisbaenia Group: The Bizarre and Enigmatic Underground Reptiles

The world of squamates is full of surprises, and among its most mysterious residents are the Amphisbaenians.

These are not your typical lizards; in fact, their peculiar features and underground lifestyles set them apart in a class of their own.

In this section, we unearth the fascinating world of Amphisbaenia, exploring their unique characteristics and shedding light on the families that make up this group.

Delving into the World of Amphisbaenia

The name ‘Amphisbaenia’ might not be as familiar to many as ‘lizards’ or ‘snakes,’ but this group of reptiles certainly deserves recognition.

Derived from the Greek term meaning ‘both ways,’ it hints at the peculiar, almost worm-like appearance of these creatures, which often makes it hard to distinguish their head from their tail at first glance.

Amphisbaenians are essentially adapted for a burrowing lifestyle. They’ve done away with limbs or have highly reduced limbs, which aids in their underground navigation.

Their eyes are often small and covered by translucent scales, as vision is not a primary sense in the dark, subterranean world they inhabit.

Unique Features that Set Amphisbaenians Apart

When we think of reptiles, we often picture scaly creatures basking in the sun. Amphisbaenians, however, are a break from this norm.

Their bodies are ringed, much like earthworms, which facilitates their movement through soil. Their skulls are robust, allowing them to push through the ground and feed on small invertebrates.

Furthermore, to aid in their burrowing, many amphisbaenians possess a unique, spade-like structure on the head, termed the ‘cephalic shield.’ This adaptation allows them to effectively “dig” through the substrate, creating tunnels and chambers.

The Families Beneath the Surface

Amphisbaenians are classified into several families, each with its own set of peculiarities. The most widespread family is the Amphisbaenidae, often termed the “worm lizards.”

Then we have the Trogonophidae, recognized by their scale patterns and distribution across Africa and the Middle East. The Bipedidae family, as the name suggests, consists of amphisbaenians that have retained two forelimbs, a feature that is particularly odd given the limbless nature of most members in this group.

Rhineuridae is primarily restricted to North America and is known for its unique jaw structure. Each of these families offers a snapshot into the incredible adaptations and evolutionary paths the Amphisbaenia group has undertaken.

Amphisbaenia Families

| Family Name | Common Name | Example Species (Common Name / Latin) |

|---|---|---|

| Amphisbaenidae | Tropical worm lizards | Darwin’s worm lizard (Amphisbaena darwinii) |

| Bipedidae | Bipes worm lizards | Mexican mole lizard (Bipes biporus) |

| Blanidae | Mediterranean worm lizards | Mediterranean worm lizard (Blanus cinereus) |

| Cadeidae | Cuban worm lizards | Cadea blanoides |

| Rhineuridae | North American worm lizards | North American worm lizard (Rhineura floridana) |

| Trogonophidae | Palearctic worm lizards | Checkerboard worm lizard (Trogonophis wiegmanni) |

As we continue our journey through the diverse realm of squamates, it becomes increasingly evident that nature, in its infinite wisdom, has crafted creatures for every niche, nook, and cranny of our planet.

The Amphisbaenians serve as a testament to this diversity, thriving beneath our feet, unseen and often underappreciated.

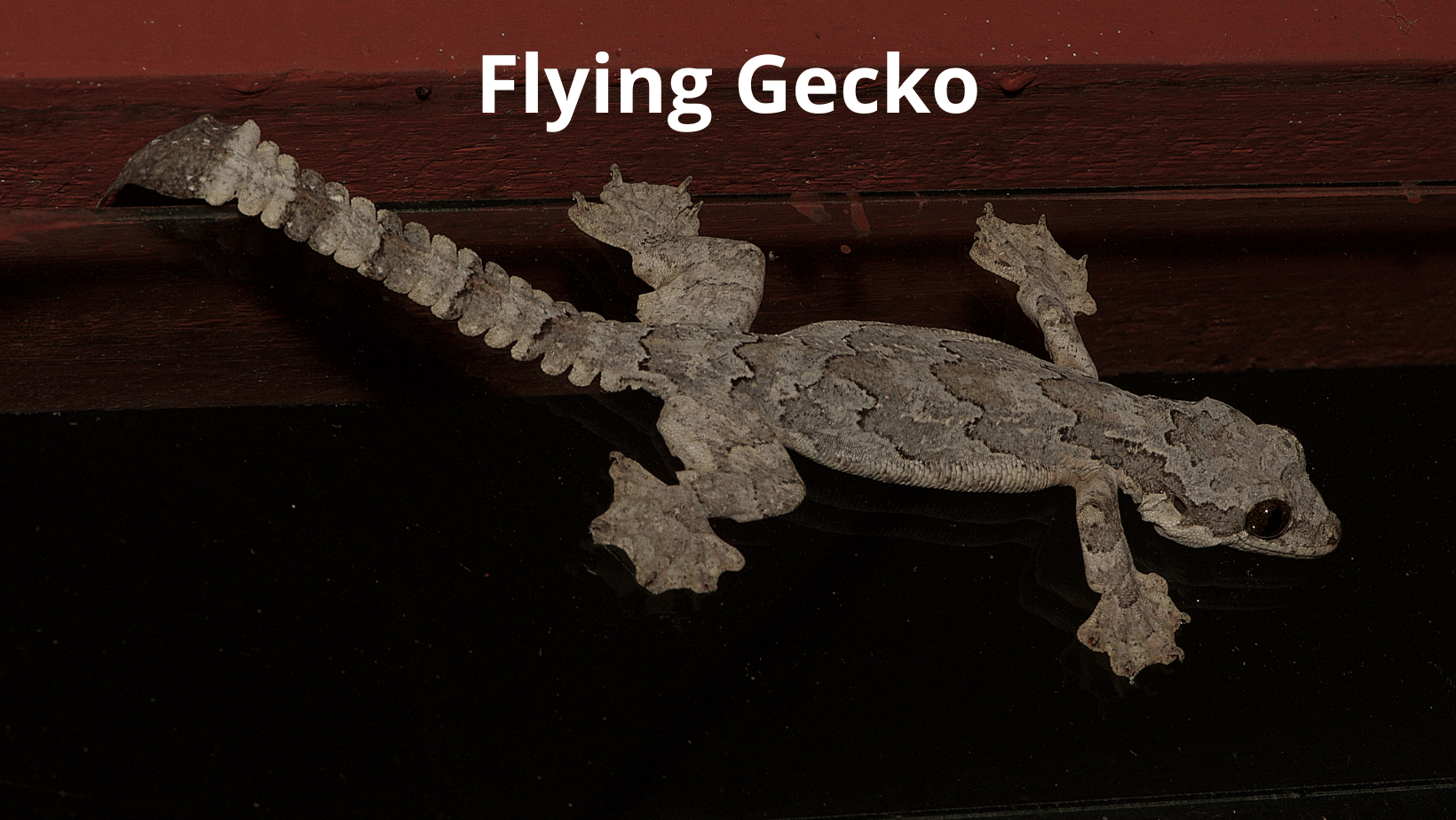

Gekkota (Including Dibamia) Group

Gekkota is a suborder that has garnered significant attention and admiration, primarily because it houses the ever-popular geckos. Their unique traits and behaviors, combined with the intriguing inclusion of Dibamia, make this group one of the most fascinating among squamates.

Overview of Geckos and Their Popularity

Geckos are undoubtedly among the most recognized reptiles globally, with their presence not only in diverse habitats but also in popular culture. From movies and books to brand mascots, these charming reptiles have found their way into the hearts of many. Their large, expressive eyes, combined with their diverse array of vibrant colors and patterns, make them stand out in the reptile kingdom. As nocturnal creatures, geckos possess a set of adaptations that allow them to navigate their surroundings with finesse and stealth.

Morphological Traits That Define Gekkota Group

Geckos, like other members of the Gekkota suborder, have unique morphological traits that distinguish them from other reptiles. One of the most notable features is their lack of eyelids. Instead, they have a transparent membrane that they clean by licking. This, coupled with their vertically slit pupils, equips them for their nocturnal lifestyle. Additionally, many gecko species boast adhesive toe pads that allow them to cling to and climb a wide range of surfaces, from slick glass to rough walls. This remarkable ability is attributed to the microscopic hairs on their feet, known as setae, which facilitate the exploitation of van der Waals forces to achieve adhesion.

The Inclusion of Dibamia and Its Significance

Dibamia, though lesser-known than geckos, play a significant role within the Gekkota suborder. These burrowing, legless lizards are an example of convergent evolution, where distinct groups of organisms independently evolve similar features due to analogous environmental pressures. The inclusion of Dibamia in Gekkota underscores the vast diversity of this suborder. Moreover, it emphasizes the importance of molecular and genetic research in the correct classification of species. As scientists have delved deeper into squamate relationships, it has become evident that external morphology alone does not always offer a complete picture of evolutionary relationships.

Gekkota Families

| Family Name | Common Name | Example Species |

|---|---|---|

| Carphodactylidae | Kluge, 1967 | Southern padless geckos (Thick-tailed gecko – Underwoodisaurus milii) |

| Dibamidae | Boulenger, 1884 | Blind lizards (Dibamus nicobaricum) |

| Diplodactylidae | Underwood, 1954 | Australasian geckos (Golden-tailed gecko – Strophurus taenicauda) |

| Eublepharidae | Boulenger, 1883 | Eyelid geckos (Common leopard gecko – Eublepharis macularius) |

| Gekkonidae | Gray, 1825 | Geckos (Madagascar giant day gecko – Phelsuma grandis) |

| Phyllodactylidae | Gamble et al., 2008 | Leaf finger geckos (Moorish gecko – Tarentola mauritanica) |

| Pygopodidae | Boulenger, 1884 | Flap-footed lizards (Burton’s snake lizard – Lialis burtonis) |

| Sphaerodactylidae | Underwood, 1954 | Round finger geckos (Fantastic least gecko – Sphaerodactylus fantasticus) |

Iguania Group

The Iguania suborder or group represents a diverse assembly of lizards known for their stunning appearances and widespread distribution. From deserts to rainforests, members of this suborder have adapted to a myriad of environments. Let’s dive deep into the world of Iguania, uncovering its notable members, habitats, and the various families it encompasses.

Introduction to This Widespread and Diverse Group

Iguanians are a predominant faction within the lizard community, accounting for roughly a third of all lizard species. The group spans continents and environments, with members having evolved to suit various habitats and niches. Characterized by acrodont dentition where the teeth are fused to the top of the jaw, Iguanians have a distinct edge in their dietary habits. From the iconic Iguanas sunning themselves on Caribbean beaches to the fierce-looking Thorny Devils of the Australian deserts, the members of this group showcase an exceptional range in size, appearance, and behavior.

Notable Species and Their Habitats

While Iguanians are found worldwide, certain species stand out because of their unique attributes or significant cultural impacts. The Green Iguana, for instance, has made its mark not just in Central and South American forests but also in the pet trade, revered for its calm demeanor and striking appearance. On the other hand, the Anoles, often seen in the Americas, exhibit a variety of vibrant colors and have a knack for territorial displays using their dewlaps. The Old World’s Agamas are a force to be reckoned with as well, displaying dynamic social structures and intricate mating rituals in the African and Asian landscapes. These are but a few examples that exhibit the extensive adaptability and versatility of the Iguanians in various habitats.

Families under the Iguania Umbrella

The richness of the Iguania suborder is further accentuated by the families it envelopes. The two primary families that dominate this group are Iguanidae (which includes iguanas) and Agamidae (encompassing the agamas). These families, though geographically distinct with Iguanidae primarily in the Americas and Agamidae in Africa and Asia, share evolutionary histories and morphological similarities. There’s also the Chamaeleonidae family, better known as chameleons, recognized for their zygodactylous feet, prehensile tails, and unparalleled ability to change skin color. Each family under the Iguania suborder contributes to the diversity and ecological significance of this remarkable group.

| Family Name | Common Name | Example species |

|---|---|---|

| Agamidae | Agamas | Eastern bearded dragon (Pogona barbata) |

| Chamaeleonidae | Chameleons | Veiled chameleon (Chamaeleo calyptratus) |

| Corytophanidae | Casquehead lizards | Plumed basilisk (Basiliscus plumifrons) |

| Crotaphytidae | Collared and leopard lizards | Common collared lizard (Crotaphytus collaris) |

| Dactyloidae | Anoles | Carolina anole (Anolis carolinensis) |

| Hoplocercidae | Wood lizards or clubtails | Enyalioides binzayedi |

| Iguanidae | Iguanas | Marine iguana (Amblyrhynchus cristatus) |

| Leiocephalidae | Curly-tailed lizards | Hispaniolan masked curly-tailed lizard (Leiocephalus personatus) |

| Leiosauridae | Leiosaurid lizards | Enyalius bilineatus |

| Liolaemidae | Tree iguanas, snow swifts | Shining tree iguana (Liolaemus nitidus) |

| Opluridae | Malagasy iguanas | Chalarodon madagascariensis |

| Phrynosomatidae | Earless, spiny, tree, side-blotched and horned lizards | Greater earless lizard (Cophosaurus texanus) |

| Polychrotidae | Bush anoles | Brazilian bush anole (Polychrus acutirostris) |

| Tropiduridae | Neotropical ground lizards | Microlophus peruvianus |

Lacertoidea (Excluding Amphisbaenia) Group

The Lacertoidea is a fascinating superfamily within the world of lizards, notable for its diversity and adaptability. Although many associate Lacertoidea with the commonly known “true lizards” of Europe and Asia, its range and diversity are vast. In this section, we’ll delve into the intriguing characteristics of this group, understand the distinction from Amphisbaenia, and shed light on the families that make up the Lacertoidea superfamily.

Distinguishing Features of This Group

Lacertoidea, commonly known as lacertoids, possess a set of distinguishing features that set them apart in the reptilian realm. These lizards typically have long bodies, slender tails, and most have well-developed limbs. Their eyes, protected by movable eyelids, give them a keen sense of vision, and many species also boast vibrant and striking color patterns. Their scales, usually smooth or slightly keeled, add to their sleek appearance. Furthermore, lacertoids are primarily insectivorous, using their agile bodies and rapid movements to chase down and capture prey.

Understanding the Exclusion of Amphisbaenia

While it might seem perplexing to some, the exclusion of Amphisbaenia from Lacertoidea is rooted in their evolutionary divergence. Though both groups belong to the larger Squamata order, their evolutionary paths and morphological differences are significant. Amphisbaenians are burrowing creatures, often referred to as “worm lizards” due to their elongated, limbless, or nearly limbless bodies – a stark contrast to the often limbed and surface-dwelling lacertoids. Their distinct lifestyles, habitats, and evolutionary histories warranted the separation of these groups in taxonomical classifications.

Lacertoidea Families and Their Unique Traits

The Lacertoidea superfamily is constituted by several families, each with its own set of unique characteristics:

- Alopoglossidae – This family is relatively lesser-known when compared to some of its counterparts. Distributed mainly in Central and South America, they are sleek lizards with specific adaptations to their respective environments. Their appearance often resembles leaf litter or twigs, providing them with a unique camouflage against potential predators.

- Gymnophthalmidae – Often referred to as spectacled lizards or microteiids due to their small size, these lizards predominantly inhabit South America. Many species in this family are adapted to burrowing, with reduced limbs and streamlined bodies.

- Lacertidae – Often termed as the ‘true lizards’, this is the largest family within Lacertoidea. Found mainly in Europe and Asia, they’re known for their agility and vivid colors. The common Wall Lizard is a popular representative of this family.

- Teiidae – Encompassing the whiptails and tegus, these lizards are predominantly found in the Americas. Recognized for their large size (in the case of tegus) and elongated tails, they’re versatile hunters, with some species having a varied diet including fruits and small animals.

Each family within the Lacertoidea contributes to the ecological tapestry of their respective habitats, playing vital roles as predators and, in turn, prey, in their ecosystems.

| Family | Common Names | Example Species |

|---|---|---|

| Alopoglossidae | Alopoglossid lizards | Alopoglossus vallensis |

| Gymnophthalmidae | Spectacled lizards | Bachia bicolor |

| Lacertidae | Wall lizards | Ocellated lizard (Lacerta lepida) |

| Teiidae | Tegus and whiptails | Gold tegu (Tupinambis teguixin) |

Anguimorpha Group – The Diverse World of Specialist Lizards

Anguimorpha represents a captivating suborder within the realm of squamates. This subgroup is not only known for its distinct morphology but also its evolutionary significance. Comprising various families, each with its unique traits, Anguimorpha serves as a testament to the adaptive prowess of squamates.

Delving into the World of Anguimorpha

Anguimorpha, at first glance, might seem like just another group of lizards. However, its members have carved out unique niches across various ecosystems, displaying an incredible range of adaptations. These lizards are characterized by elongated bodies, and some even lack limbs entirely, closely resembling snakes. This convergent evolution with serpents showcases the fascinating ways in which different groups can arrive at similar solutions when confronted with analogous ecological challenges.

Characteristics and Evolutionary Significance

The members of Anguimorpha have evolved a plethora of characteristics that set them apart from other lizards. Notably, many have highly specialized tongues, employed in various sensory roles. Their evolutionary journey also highlights several instances of parallel evolution, where different groups within Anguimorpha developed similar adaptations independently. This is particularly evident in their feeding strategies, with several species evolving long, extensible tongues to capture prey, mirroring the evolutionary path seen in some geckos and chameleons.

The evolutionary significance of Anguimorpha doesn’t end there. As we delve deeper into the fossil record, we find evidence of anguimorphs occupying a variety of roles in ancient ecosystems. Their evolutionary history offers valuable insights into how reptiles diversified and adapted over millions of years, reinforcing their importance in the broader context of vertebrate evolution.

Overview of Families within Anguimorpha

The Anguimorpha suborder boasts an array of families, each bringing a unique set of traits and adaptations to the table. For instance, the Anguidae family, also known as glass lizards, have limbless members that resemble snakes, with the capability to break off their tails when threatened. The Helodermatidae family, on the other hand, contains the infamous Gila monster and Mexican beaded lizard, which are among the few venomous lizards in the world.

Another notable family within Anguimorpha is the Varanidae, which houses the monitor lizards. This family includes the Komodo dragon, the largest living lizard on Earth. The diverse range of sizes, habitats, and feeding strategies exhibited by these families underscores the adaptive versatility of Anguimorpha, making it a subject of keen interest for herpetologists and evolutionary biologists alike.

Scincoidea Group – Skinks and Their Intriguing Kin

Scincoidea, a suborder primarily known for its skinks, is a testament to the adaptive abilities of squamates. As one delves deeper into this world, a tapestry of evolutionary wonder unfolds, showcasing how these reptiles have carved out their niches in diverse ecosystems across the globe. Within this group, various families, each with its distinctive characteristics, come together to paint a comprehensive picture of Scincoidea’s place in the world of reptiles.

A Look at the Fascinating World of Skinks and Their Relatives

Skinks, with their sleek, elongated bodies and reduced limb sizes, are often mistakenly seen as simple creatures. Yet, they encompass a vast range of species, each with its quirks and adaptations. From the sand-diving skinks of deserts, which “swim” through the sand, to the arboreal species navigating tree canopies, the diversity is truly astounding.

Skinks are often characterized by their shiny, overlapping scales which give them a streamlined appearance. This is particularly useful for species that burrow or navigate through dense vegetation. Additionally, some species have evolved unique ways to avoid predation; a well-known example is their ability to shed their tails, leaving a wriggling distraction behind for potential predators.

Morphological and Ecological Traits

Skinks, by and large, share a set of morphological traits, such as their elongated bodies, reduced limbs, and a distinct head shape. Yet, within these general parameters, there’s considerable variation. For example, some skinks possess fully functional legs, while others might have tiny, vestigial limbs or none at all. Their eyes, often with a shimmering quality, can vary in size depending on whether the species is nocturnal or diurnal.

Ecologically, skinks are versatile. They occupy a variety of habitats, from arid deserts to tropical forests. Their diets, too, range from herbivorous to insectivorous and even carnivorous in some larger species. This ecological adaptability has allowed skinks to colonize a variety of environments around the world, making them one of the most widespread and successful lizard groups.

Families that Constitute Scincoidea

While the Scincidae family, housing the skinks, is the most prominent within the Scincoidea suborder, it’s essential to recognize the other families that enrich this group’s diversity. Families like Cordylidae, with their armored lizards, bring a different set of adaptations to the table. The Gerrhosauridae family, known for plated lizards, displays another unique take on the scincoid body plan.

These families, together with the skinks, showcase the impressive evolutionary journey of the Scincoidea suborder. From the vast deserts of Africa to the dense forests of Asia and Australia, members of this group have found ways to thrive and adapt, reflecting the sheer diversity and adaptability inherent to squamates.

| Family | Common Names | Example Species |

|---|---|---|

| Cordylidae | Girdled lizards | Girdle-tailed lizard (Cordylus warreni) |

| Gerrhosauridae | Plated lizards | Sudan plated lizard (Gerrhosaurus major) |

| Scincidae | Skinks | Western blue-tongued skink (Tiliqua occipitalis) |

| Xantusiidae | Night lizards | Granite night lizard (Xantusia henshawi) |

Alethinophidia Group – Delving into the Realm of True Snakes

The Alethinophidia, often referred to as “true snakes”, represent a major portion of the serpent world. They capture our imaginations, evoke our deepest fears, and sometimes even earn our admiration. As we embark on this journey to understand Alethinophidia better, we’ll uncover the key traits that define them, meet some of their notable members, and dive into the diverse families that make up this group.

Introduction to This Significant Snake Group

In the vast world of serpents, the Alethinophidia holds a place of prominence. While the term “true snakes” might seem a misnomer given that all snakes are “true” in their own right, it’s a term that denotes the vast majority of snake species we’re familiar with. Excluding the blind snakes of the Scolecophidia group, virtually all other snakes fall under the Alethinophidia umbrella.

These snakes have made their presence known across the globe, from the rainforests of the Amazon to the deserts of Africa. They range in size from the petite sunbeam snake to the formidable reticulated python, the longest snake in the world. Their ecological roles are just as varied, with some being apex predators and others playing crucial roles in controlling pest populations.

Key Characteristics and Species

One of the distinguishing features of Alethinophidia is the presence of a functional left lung, which is either similar in size to the right lung or slightly smaller. This contrasts with many members of Scolecophidia, which often have a reduced or absent left lung. Additionally, Alethinophidia typically have more complex ventral scales, aiding in locomotion.

Some standout species in this group include the Green Anaconda, the heaviest snake globally, and the King Cobra, the world’s longest venomous snake. Each species, with its unique adaptations and behaviors, adds a different hue to the vibrant tapestry of Alethinophidia. Whether it’s the mesmerizing dance of the Indian Rat Snake or the swift strike of the Black Mamba, the species within this group never cease to amaze.

Families within Alethinophidia and Their Relevance

The Alethinophidia is home to numerous snake families, each bringing its evolutionary tales to the table. Families like Boidae, encompassing boas and anacondas, and Pythonidae, housing the pythons, are just the tip of the iceberg. There’s also the Colubridae, the largest snake family with its non-venomous members; the Viperidae, with its iconic vipers and pit vipers; and the Elapidae, containing cobras, mambas, and coral snakes, to name a few.

Each family, with its lineage and evolutionary history, offers insights into the adaptability and survival prowess of snakes. They highlight the diverse strategies these reptiles have employed to conquer varied habitats and ecological niches. From constrictors that rely on brute strength to venomous species that have perfected the art of chemical warfare, the families of Alethinophidia showcase the incredible diversity and complexity of the snake world.

| Family | Common names | Example species |

|---|---|---|

| Acrochordidae | File snakes | Marine file snake (Acrochordus granulatus) |

| Aniliidae | Coral pipe snakes | Burrowing false coral (Anilius scytale) |

| Anomochilidae | Dwarf pipe snakes | Leonard’s pipe snake, (Anomochilus leonardi) |

| Boidae | Boas | Amazon tree boa (Corallus hortulanus) |

| Bolyeriidae | Round Island boas | Round Island burrowing boa (Bolyeria multocarinata) |

| Colubridae | Colubrids | Grass snake (Natrix natrix) |

| Cylindrophiidae | Asian pipe snakes | Red-tailed pipe snake (Cylindrophis ruffus) |

| Elapidae | Cobras, coral snakes, mambas, kraits, sea snakes, sea kraits, Australian elapids | King cobra (Ophiophagus hannah) |

| Homalopsidae | Indo-Australian water snakes, mudsnakes, bockadams | New Guinea bockadam (Cerberus rynchops) |

| Lamprophiidae | Lamprophiid snakes | Bibron’s burrowing asp (Atractaspis bibroni) |

| Loxocemidae | Mexican burrowing snakes | Mexican burrowing snake (Loxocemus bicolor) |

| Pareidae | Pareid snakes | Perrotet’s mountain snake (Xylophis perroteti) |

| Pythonidae | Pythons | Ball python (Python regius) |

| Tropidophiidae | Dwarf boas | Northern eyelash boa (Trachyboa boulengeri) |

| Uropeltidae | Shield-tailed snakes, short-tailed snakes | Cuvier’s shieldtail (Uropeltis ceylanica) |

| Viperidae | Vipers, pitvipers, rattlesnakes | European asp (Vipera aspis) |

| Xenodermidae | Odd-scaled snakes and relatives | Khase earth snake (Stoliczkia khasiensis) |

| Xenopeltidae | Sunbeam snakes | Sunbeam snake (Xenopeltis unicolor) |

Scolecophidia Group – The Enigmatic World of Blind Snakes and Their Kin

Within the expansive realm of squamates, the Scolecophidia, or the “blind snakes”, occupy a unique niche. These often-overlooked creatures lead a secretive life, spending much of their time burrowed underground. Their distinct adaptations and lifestyles make them a fascinating subject of study. In this segment, we’ll traverse the world of Scolecophidia, discuss the inclusion of the Anomalepidae, and delve into the families that characterize this group.

Blind Snakes and Relatives

The term “blind snake” may suggest these creatures lack vision entirely. However, this isn’t strictly the case. While their eyes are significantly reduced, often appearing as mere dark spots beneath translucent or opaque scales, they can detect changes in light intensity. This is more than sufficient for their subterranean lifestyle, where acute vision wouldn’t offer much advantage.

The physical adaptations of blind snakes make them well-suited for a life of burrowing. They possess small, smooth, and shiny scales, giving them a worm-like appearance. This not only facilitates easy movement through soil but also makes them slippery prey, difficult for predators to grasp. Most blind snakes are insectivores, feeding primarily on ants and termites, making them essential controllers of insect populations.

Anomalepidae

The Anomalepidae, commonly known as the “primitive blind snakes,” are a small family within the Scolecophidia. While they share many traits with other blind snakes, such as reduced vision and a subterranean lifestyle, their inclusion in discussions about Scolecophidia is vital due to their primitive characteristics. These features offer insights into the evolutionary journey of blind snakes and their adaptations over time.

Anomalepids, native to Central and South America, showcase certain anatomical traits that are believed to be ancestral features. Their distinct jaw structures and the presence of light-sensitive cells in their rudimentary eyes offer intriguing clues about the evolution of burrowing adaptations in snakes. Understanding Anomalepidae is akin to peeling back the layers of evolutionary history, revealing the initial steps that led to the diversity of blind snakes we observe today.

Families and Their Distinguishing Features

Scolecophidia encompasses several families, each contributing its unique set of characteristics and adaptations. Apart from the aforementioned Anomalepidae, there are families like Typhlopidae, which contains the majority of blind snake species. Their members, spread across various continents, range in size from tiny species to ones reaching almost a meter in length.

Then there’s the Leptotyphlopidae, the slender blind snakes, which are even more worm-like in their appearance and have unique adaptations for feeding on soft-bodied prey. Another family worth mentioning is Xenotyphlopidae, a lesser-known group with very few species but of great interest to herpetologists due to their rare occurrences and limited geographical distribution.

Each family within Scolecophidia, with its set of morphological and behavioral traits, paints a comprehensive picture of the adaptations and survival strategies employed by these cryptic creatures. Their lifestyles might be shrouded in darkness, but the insights they provide into the world of reptiles are illuminating.

| Family Name | Common names | Example species |

|---|---|---|

| Anomalepidae | Dawn blind snakes | Dawn blind snake (Liotyphlops beui) |

| Gerrhopilidae | Indo-Malayan blindsnakes | Andaman worm snake (Gerrhopilus andamanensis) |

| Leptotyphlopidae | Slender blind snakes | Texas blind snake (Leptotyphlops dulcis) |

| Typhlopidae | Blind snakes | European blind snake (Typhlops vermicularis) |

| Xenotyphlopidae | Malagasy blind snakes | Xenotyphlops grandidieri |

Conclusion – A Tribute to the Majesty and Evolutionary Marvel of Squamates

The journey through the world of squamates reveals an intricate tapestry of life that has thrived, evolved, and diversified over millions of years. From the depths of the soil where blind snakes burrow to the canopies where geckos scamper, squamates occupy virtually every conceivable niche on our planet. This concluding section is not just a reflection on the diversity and marvel of squamates but also a call to recognize their importance and the pressing need for their conservation.

Reflecting on the Vast Diversity and Evolutionary Marvel of Squamates

The grandeur of squamates cannot be overstated. They represent one of the most diverse groups of vertebrates, with a staggering number of species showcasing a myriad of forms, behaviors, and ecological roles. Their evolutionary journey, spanning over hundreds of millions of years, has resulted in an impressive array of adaptations, from the venomous fangs of vipers to the adhesive toe pads of geckos.

Moreover, squamates serve as a testament to nature’s ability to innovate and adapt. The vivid colors of a chameleon, the elongated body of a snake, or the burrowing prowess of the Amphisbaenia, each tells a tale of evolutionary pressures and the relentless drive to survive and reproduce. Their existence enriches our planet and offers invaluable insights into the intricate workings of evolution, ecology, and biology.

The Importance of Conservation Efforts for These Reptiles

In the modern era, where habitat destruction, climate change, and human encroachments are rampant, the very survival of many squamate species hangs in the balance. Every lost species or habitat is not just a reduction in biodiversity but also an irretrievable loss of evolutionary history and ecological functionality.

Squamates play crucial roles in ecosystems, be it as predators controlling pest populations, or as prey supporting higher trophic levels. Their loss can have cascading effects on ecosystems, leading to imbalances that can be challenging, if not impossible, to rectify. Hence, the conservation of squamates is not just about saving individual species but preserving the health and balance of entire ecosystems.

As we conclude this exploration, let it be a reminder that our understanding and appreciation of squamates should translate into tangible actions. Active conservation, habitat restoration, and spreading awareness are paramount if we hope to coexist with these remarkable creatures and ensure their survival for generations to come.